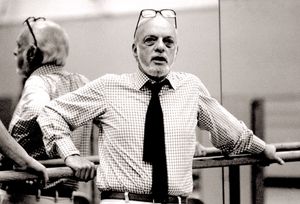

The news of Hal Prince’s death hit the theater community on Wednesday like a bomb of sorrow, love and gratitude for a life that generously gave everything he had to building musical theater up to its historically highest level. From reading the testimonies of those who were close to him, it is clear that he not only gave freely of his artistic genius, but he invested in relationships with many young artists all around him, encouraging and inspiring them to carry his torch of creative excellence. The news of his passing has hit me with a weight of sadness I did not expect. I never knew him personally, never worked with him, but his work affected me so deeply, I never fully realized how much until now. As I process this grief, I realize that I’m not merely grieving the loss of a person, but perhaps of a movement of musical theater that shaped it into being the form of art and entertainment I came to love enough to make it my livelihood.

If you don’t know who Hal Prince is, you can read his obituary here (I recommend watching the video interview). His legacy to Broadway musical theater is unparalleled, having won a record-holding 21 Tony awards (no one else even comes close) as a director and producer. If you haven’t heard of his name, you’ve most definitely heard of some of the shows he either directed, produced, or both: Phantom of the Opera, Evita, West Side Story, Cabaret, Fiddler on the Roof, The Pajama Game, Damn Yankees, Company, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd - the list goes on and on. But not only did he have a pivotal role in bringing these legendary shows life, he pioneered the roles of producer and director as being a co-creator. His collaborations with Stephen Sondheim brought a level of intelligence and sophistication to musical theater that was unprecedented, but more importantly, challenged audiences to look at and question what was truly good and beautiful in the world. Rodgers and Hammerstein laid the foundations for stories of truth and beauty to be presented through the mediums of song, dance, and dialogue, and then Prince and Sondheim built on that foundation with a new level of courage and boldness.  Company, which first opened on Broadway in 1970, was probably the first musical to truly explore the complexities of choosing a spouse without the “happily ever after” in the end. It gave real permission to normal married people to acknowledge that even happy marriages have issues, and being single can feel both suffocating and liberating at the same time. It didn’t attempt to give a clear answer that could sum up the whole problem in a neat little bow. Prior to this, musicals typically either ended in a happy marriage, or were an escape from the real world altogether and just didn’t deal with any issues at all (exceptions in the 1950s-60s include Gypsy, West Side Story, and Fiddler on the Roof, the latter two of which Hal Prince produced). Follies, Pacific Overtures, A Little Night Music, and Sweeney Todd followed suit, leaving audiences challenged to look at their own hearts, or lives, or to look at history, in a new light. Even Merrily We Roll Along, which was famous for being the colossal Prince/Sondheim flop, has a cult following thanks to its very real theme of friendship sacrificed at the altar of success. Cabaret, Prince’s collaboration with writing team Kander and Ebb of Chicago fame, brought the use of metaphor in musical theater to a new level with its representation of Berlin in the 1930’s that starts out as what appears to be a super tacky and seedy cabaret show, and ends with several story lines culminating in previously lovable characters becoming Nazi sympathizers, Nazis themselves, or clueless and complacent bystanders during the rise of Nazi Germany.

Company, which first opened on Broadway in 1970, was probably the first musical to truly explore the complexities of choosing a spouse without the “happily ever after” in the end. It gave real permission to normal married people to acknowledge that even happy marriages have issues, and being single can feel both suffocating and liberating at the same time. It didn’t attempt to give a clear answer that could sum up the whole problem in a neat little bow. Prior to this, musicals typically either ended in a happy marriage, or were an escape from the real world altogether and just didn’t deal with any issues at all (exceptions in the 1950s-60s include Gypsy, West Side Story, and Fiddler on the Roof, the latter two of which Hal Prince produced). Follies, Pacific Overtures, A Little Night Music, and Sweeney Todd followed suit, leaving audiences challenged to look at their own hearts, or lives, or to look at history, in a new light. Even Merrily We Roll Along, which was famous for being the colossal Prince/Sondheim flop, has a cult following thanks to its very real theme of friendship sacrificed at the altar of success. Cabaret, Prince’s collaboration with writing team Kander and Ebb of Chicago fame, brought the use of metaphor in musical theater to a new level with its representation of Berlin in the 1930’s that starts out as what appears to be a super tacky and seedy cabaret show, and ends with several story lines culminating in previously lovable characters becoming Nazi sympathizers, Nazis themselves, or clueless and complacent bystanders during the rise of Nazi Germany.

Musical theater on Broadway was not at its economic peak in the era when Hal Prince’s genius was on the rise. There were several reasons as to why this was: the economic recession of the 1970s; Times Square was not exactly a family-friendly place from the 1970’s - late 1990’s; and perhaps partly due to Hal Prince’s influence, the audience appeal for the kinds of musicals being produced tended to be limited more to the New York theater circles and intellectual elite. This was of course before the digital age enabled social media to expose the masses across the country to what was going on in America’s musical theater center, New York City. However, perhaps because artists didn’t feel so beholden to the economic machine of the industry as we know it today, the up-and-coming artistic geniuses of the time were able to find outlets where their creative ideas could germinate. This was the very environment in  which the great Michael Bennet created A Chorus Line, starting from a roomful of dancers sharing their war stories and then workshopping those stories as songs and dances to create one of the greatest musicals of all time. Similarly, Hal Prince had room to be artistically bold, and thus he pushed the envelope of what musical theater could do in these last decades of the 20th Century. The result was always a compelling night of theater that would envelop the audience and perhaps even change us. It would capture our imaginations in a way that not only caused us to escape reality for a couple of hours, but when we left, we looked at the world, and/or our own hearts differently. Even when Prince did create profitable, enduring works of theater such as Phantom of the Opera, Evita, and his 1996 revival of Show Boat, it was with a drive for artistry that gave the audience a complete - and original - rapturous experience through story, drama, and visual stimulus that all worked together to take our imaginations prisoner.

which the great Michael Bennet created A Chorus Line, starting from a roomful of dancers sharing their war stories and then workshopping those stories as songs and dances to create one of the greatest musicals of all time. Similarly, Hal Prince had room to be artistically bold, and thus he pushed the envelope of what musical theater could do in these last decades of the 20th Century. The result was always a compelling night of theater that would envelop the audience and perhaps even change us. It would capture our imaginations in a way that not only caused us to escape reality for a couple of hours, but when we left, we looked at the world, and/or our own hearts differently. Even when Prince did create profitable, enduring works of theater such as Phantom of the Opera, Evita, and his 1996 revival of Show Boat, it was with a drive for artistry that gave the audience a complete - and original - rapturous experience through story, drama, and visual stimulus that all worked together to take our imaginations prisoner.

In the late 1990’s, there was a shift away from musical theater being driven by a hunger for works of artistic brilliance, and a move towards the industry being a profitable economic enterprise. This was in part due to Disney’s takeover of the New Amsterdam theater on 42nd Street, and thus the corporate entertainment giant’s continual Broadway presence, now in multiple theaters concurrently, season after season. Not only Disney, but other Broadway producers joined forces to create producing conglomerates, rather than one producer taking on the entire financial and administrative burden for a given show. The reasoning is understandable, as Broadway productions are risky financial ventures, frequently losing money. So in one sense, this shift saved the economy of Broadway musical theater.

However, in another sense, something seems to also have been lost. Hal Prince and his contemporaries had a mantle of artistic boldness that I am having trouble finding today. There’s a subtle quality in the works of “the Prince era” of storytelling, or even concept-presenting, without spoon-feeding the audience the clear opinions and/or worldview of the creative team. It was creative storytelling that was not predictable. My emotional response was not predictable. When I used to see a Hal Prince show for the first time, I didn’t know what it would leave me with.

However, in another sense, something seems to also have been lost. Hal Prince and his contemporaries had a mantle of artistic boldness that I am having trouble finding today. There’s a subtle quality in the works of “the Prince era” of storytelling, or even concept-presenting, without spoon-feeding the audience the clear opinions and/or worldview of the creative team. It was creative storytelling that was not predictable. My emotional response was not predictable. When I used to see a Hal Prince show for the first time, I didn’t know what it would leave me with.

I hate to say it, but I find this not to be the case so much anymore. While there are many brilliant artists in the theater community today, I don’t usually find myself surprised by what a show left me feeling or thinking anymore. There are exceptions to this rule. Hamilton, Bright Star, and Next to Normal all broke it handily for me. But I often find that even when a show is done with breathtaking directorial choices, expertly crafted musical arrangements, and deeply complex performances by the cast, I may leave feeling impressed by the work, but rarely surprised by the impression it made on me. In fact, it is often too familiar an impression - one I predicted because I have felt it so many times before.

THIS, in my opinion - this ability to leave the audience surprised, alarmed, moved, changed, wanting to dig deeper into the meaning of life - THIS is the legacy of Hal Prince. Who is picking up this mantle among our generation? They’re out there. I look forward to seeing more of where we can trace the baton passing from Hal Prince’s hand into those of today’s brilliant musical theater minds.